Loading building details...

River Terrace Apartments

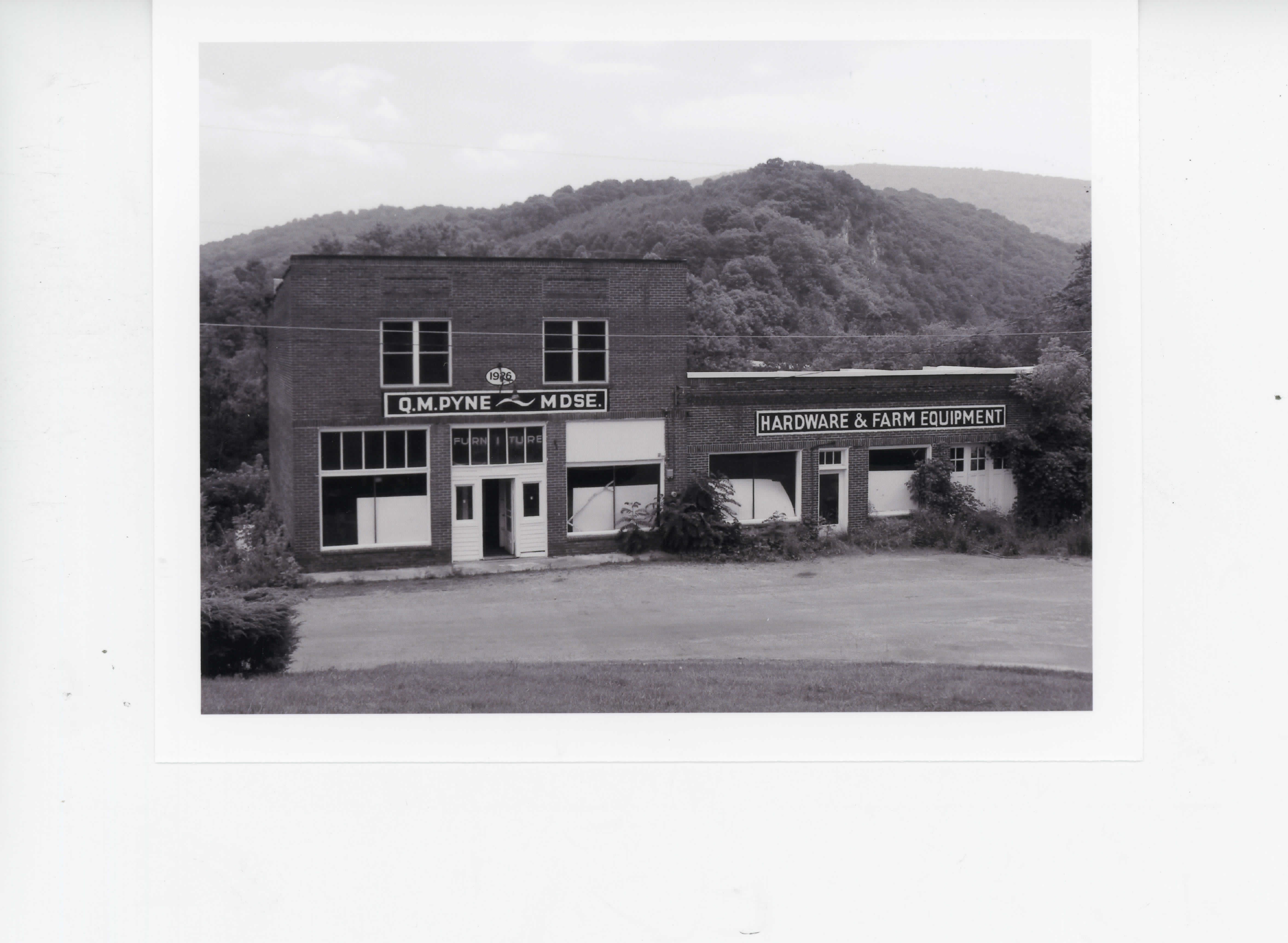

Historic Photo from NRHP Filing

National Register of Historic Places Filing

The River Terrace Apartments was constructed in 1939 for a syndicate that included property owner Wesson Seyburn and Leonard P. Reaume, of the firm of Holden & Reaume, Inc., property management. The property meets national register criteria A and C under Social History and Architecture and within the local, metropolitan Detroit context. The Neo-Georgian complex's buildings were described in a Pencil Points feature as being patterned after Rutland Lodge, Petersham, Surrey. Designed by Detroit architects Derrick & Gamber, Inc., the complex was one of the first two garden apartment complexes built in Michigan using Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loan guarantees. The complex, designed for middle-income tenants, embodies FHA planning standards for rental projects emanating from the Garden City Movement and developed beginning with the FHA's first major rental housing project, Colonial Village in Reston, Virginia, begun in 1935 shortly after the 1934 passage of the National Housing Act.

Throughout the history of Detroit, East Jefferson Avenue has been an important transportation route that follows the Detroit River and then the shoreline of Lake St. Clair northeastward from central Detroit. It continues today to be a main traffic connector and the commercial gateway leading to the prestigious neighborhoods of the Grosse Pointes and beyond. East Jefferson Avenue, the site of River Terrace Apartments, became a prestigious residential location by the later nineteenth century as leading citizens and businesspeople built large homes and established estates along it. By the early twentieth century, as Detroit's population exploded as a result of the city's auto-led industrial boom, Detroit's Gold Coast along the river became the site of some of the city's largest and most upscale apartment buildings. The building boom collapsed with the onset of the 1930s Depression. River Terrace was the first new apartment complex built along the river since the late 1920s. The River Terrace Apartments were the only riverfront apartments in Detroit to utilize the garden court design to take advantage of the riverfront site.

River Terrace's developers obtained building permit #11923 from the city March 16, 1939. Part of the site had previously been used as a base for seaplanes operating between Detroit and Cleveland. The riverfront end of the site was to be infilled with debris from city projects dumped by the city Department of Public Works during 1939 under a contract with property owner Wesson Seyburn, according to a November 1, 1938, Detroit News report. Derrick & Gamber, Inc., were architects for the project, and the general contractor was the Esslinger-Misch Co. The buildings were completed in October 1939.

The original promotional brochure for the property termed River Terrace a "distinguished residential development" that was designed to carry on the traditional styling of the nearby Indian Village neighborhood - one of the most upscale and wealthy districts in Detroit. By incorporating Georgian detailing, River Terrace echoed the style of the Georgian-Colonial Revival homes found throughout Indian Village. This association would have been a selling point for the apartments. The Georgian style generally refers to a period of architectural development in Britain and America from the early 1700s to the American Revolution - during the reign of kings George I, II, and III. Rooted in Classical design principles of ancient Rome, this English style came to America by way of British pattern books and a wave of masons, carpenters, and joiners who emigrated from England. The Georgian Revival style uses Renaissance-inspired classical symmetry, with a rectangular, strictly symmetrical, balanced facade. The central bay of the facade is often slightly projected and the center entrance is framed by a portico with columns or pilasters.

The River Terrace was featured in Pencil Points, a magazine for the architectural profession of the 1930s, which stated that "The severe Georgian design was based on that of Rutland Lodge, in Petersham, Surrey, which was built about in the middle of the Eighteenth Century." According to the article, the red face brick was chosen for its rough texture and the entrances were adapted from various Georgian examples. The River Terrace Apartments' original promotional brochure emphasized that the apartments were more like "homelike suites" and explained that the properties contained a combination of sized units ranging from studios (twenty-four), one-bedroom (118), and two-bedroom (thirty-six) up to five-room suites (eight of them) facing the riverfront. The apartments were all designed to have windows facing in at least two directions, "thus affording cross-ventilation and assuring an abundance of light and air."

The River Terrace Apartments were setting themselves apart from earlier twentieth-century apartment houses that had apartment units arranged in rows down corridors and retail stores on the first floor. The River Terrace Apartments' plan of separate apartment buildings and a private garden area - almost a private backyard - made the garden apartment a desirable new apartment style. Of course river views were emphasized in the promotional brochure, and the cover of the original promotional brochure featured a large illustration showing a sailboat on the waves.

Branson V. Gamber (1893-1949), architect and principal with his firm Derrick & Gamber, Inc., was also a spokesperson for the project. Branson Gamber was a prominent Detroit architect and served on two appointive Detroit city commissions, as well as the Professional Practice Committee of the Detroit Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (A.I.A.). Gamber was appointed Michigan Director of the Historic American Buildings Survey and later became Regional Director. The President of the A.I.A. appointed Gamber a member of the National Architectural Accrediting Board. Derrick & Gamber were responsible for designing the Federal Building in Detroit, the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Dearborn City Hall, and the Grosse Pointe High School and John D. Pierce Jr. High School in Grosse Pointe. Robert O. Derrick (1890-1961) entered into practice in 1921 after his education at Yale and Columbia Universities. After the death of business partner Gamber, he continued the firm as Robert O. Derrick and Associates and designed other buildings including Jennings Hospital in Detroit, and the Punch and Judy Theater and the Grosse Pointe Club, in Grosse Pointe.

The European housing shortage following World War I led to new European design solutions creating improved living conditions that were popularized in the Garden City Movement. The Garden City Movement was a concept initiated in late nineteenth-century England. An early exposition of Garden City principles was contained in Ebenezer Howard's 1902 book, Garden Cities of To-morrow. English Garden City planning concepts were introduced to the United States in the early twentieth century. Americans Clarence Stein and Henry Wright were instrumental in promoting Garden City planning in the 1920s. In his book Towards New Towns for America, Stein explained his process for integrating European housing solutions and American lifestyles.

Wright and Stein designed the Sunnyside Gardens complex in New York City, built in 1924-29, incorporating European Garden City design concepts. Stein felt that some alterations to European Garden City practices would make them more compatible with American needs. Sunnyside Gardens was planned and built in hopes of marketing the idea to New York City's Housing Corporation. The site's advantages included close proximity to the city center, cheap land values, and access to the city utilities. Although the Sunnyside Garden design was successful, Stein considered it a stepping-stone to his design for Radburn, New Jersey, which became America's first Garden City. The Radburn site was in Fairlawn, New Jersey, and this American Garden City design combined European Garden City concepts with tenants' need for automobiles in an area where public transportation was inadequate and expensive. Specialized routes were built for either pedestrian or motor vehicle use. Pedestrian walkways and vehicle areas were kept separate in order to keep vehicles out of view. Houses were "turned around" in order to have living quarters and sleeping rooms face towards the gardens and parks while service rooms fronted on access roads. The park was considered the "backbone" of the project.

Garden apartment design, and garden city planning, on a larger scale, provided developers with a framework within which to build more attractive and accommodating apartments, which were greatly in need in the 1930s and 1940s. The garden apartment model afforded developers the opportunity to utilize multiple buildings, avoid street frontage and embrace a courtyard, and provide off-street parking while still providing centralized services such as laundry facilities and drying yards. The result was a model that not only provided housing that was affordable and attractive, but also provided opportunity for developer profit. The new garden apartments were typically designed with repeating design modules applied to two- and three-story buildings situated along landscaped courtyards and green spaces. They offered excellent air circulation, abundant natural light and "Windows that instead of looking into the adjoining house look out upon the broad planted central area." These apartments, one advocate wrote, could provide "ready access to ... outdoor garden ... spaces; and ... eliminate all internal halls."

One of the goals of the United States government, through the Federal Housing Act, was to make the American dream of a suburban home come true for persons of low and moderate income. Because the government realized that its homeownership goals were not entirely suited for urban areas, the garden apartment requirements were established for urban construction. Though the garden apartment tenant lacked the ability to own, it was hoped that the amenities of quality construction, low-density development, and buildings placed in a park-like setting would be an attractive alternative. It was further assumed that through such development, a sense of community would evolve.

The FHA was established through the National Housing Act of 1934, part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's "New Deal" plan for America. The FHA was established as an insurance agency that cooperated with the building industry and mortgage-lending institutions in a program designed to counteract the effects of the Great Depression on the nation's housing industry and contribute to a nationwide improvement in housing standards and conditions. Those two main goals of the FHA, mortgage financing for families and the improvement of housing standards, formed the basis of the FHA program. The construction of new housing and specifically rental urban housing was a high priority for the FHA. It was noted in 1939 that the rental population had increased year by year to reach a total of 56% of all urban families, and yet the building industry had concentrated on the production of for-sale housing. As in the case of the River Terrace Apartments, FHA funding enabled the construction of housing units in urban areas where demand was high.

The FHA required developers to follow a set of housing guidelines provided under the National Housing Act. These standards addressed community, neighborhood, site, buildings, dwelling units, services, and cost. The guidelines promoted cost effectiveness and the use of familiar architectural styles. FHA rental projects had four requirements: First, they were to be large projects in order to take advantage of economies of scale in materials and labor. Second, it was preferred that the larger projects be big enough to create their own neighborhood and thus their own neighborhood characteristics. Third, employing competent architects and land-planners experienced in the design of attractive projects was a priority. Lastly, FHA projects were to be "located on large tracts of land at the edge of cities where land prices were low and families could benefit from more space between buildings, more privacy, and the absence of city noise and dirt."

The FHA's first large-scale rental housing project was "Colonial Village" in Reston, Virginia. It was constructed in four stages between 1935 and 1940 and was designed by Harvey Warwick and Frances Koenig. Intending Colonial Village to be a model for subsequent FHA-insured projects, FHA officials worked with the developers to create a prototype apartment complex displaying what they considered to be exemplary site planning, landscaping, land density, dwelling layout, construction, ventilation, and building orientation that would meet the FHA's Section 207 requirements. The Colonial Village buildings occupy only eighteen percent of the land in the apartment complex. There were a total of 1,055 apartments constructed. Rent reductions to make Colonial Village a low-cost housing project were initially seen as risky. However, the project was reported to have never lost an entire month's rent for one of its apartments in its first three years of existence.

The River Terrace Apartments complex contained a total of 178 apartments. The original rent amounts were classified as "moderate." The buildings were designed with sixteen separate entrances and staircases to give the apartment occupants a feeling of privacy. Only four units opened onto each staircase landing. Newspaper articles from 1939 stated that the architects eliminated elaborate lobbies and ballrooms in order to use more space for residential units. It was also noted that there were no business places in the apartment buildings to disturb the residents. This was an intentional decision of the designers in order to create an atmosphere of "strictly residential quietness."

Physical Description

Located on East Jefferson Avenue along the Detroit River in the one-time "Gold Coast" area of large and costly homes and apartment buildings, the River Terrace Apartments is a garden court apartment complex that is comprised of four red brick buildings of Georgian Revival design. The buildings feature one and two bedroom units with front and side entrances and are arranged around a courtyard that leads to the Detroit River. The front of the apartment complex faces East Jefferson Avenue, one of Detroit's main artery roads. The apartment units feature hardwood floors and tiled baths and for the most part retain their original wood trim and Georgian details. The Georgian Revival exteriors are notable for their use of pedimented porch designs and limestone beltcourses between the second and third floors.

The River Terrace Apartments are a "garden court" type of apartment complex comprised of four separate structures arranged around a large garden and lawn space that slopes down to the Detroit River. The buildings are three and one-half to four stories tall. Each structure has a different plan although they all share the same Georgian Revival architectural details. The flat-roof buildings are of steel frame and hollow cinder block construction faced in red brick laid in a running bond pattern. The building frontages are set back in several bays along the facades. The four buildings contain a total of 178 apartment units varying in size from two-and-a-half-room studios to five-room apartments. The River Terrace Apartments are sited to face East Jefferson Avenue, a main thoroughfare in Detroit, and address the Detroit River, to provide access to the shoreline and river views. The River Terrace Apartments are located approximately three miles from downtown Detroit, and just a short distance from the MacArthur Bridge running to Belle Isle, an island park owned by the City of Detroit. The property is in good condition and has had the windows replaced, but otherwise has had very little alteration since its construction.

The River Terrace Apartments can be described as being in the "garden court" type of apartment arrangement. That means the apartment structures are arranged around a large garden space that is for the benefit of all the tenants. The property contains a total of five and a half acres. A newspaper article at the time of construction stated that the apartment project would cover only 19 percent of the land area, thus assuring ample light for all apartments and permitting a quiet atmosphere and a large terraced garden along the riverfront. Gated entrances that can only be accessed by the residents are located on the east and west sides of the apartment buildings at East Jefferson and provide access to the residents' parking spaces and driveway along the northeastern and southwestern perimeters of the apartment complex.

The four apartment structures have substantially different footprints. Building Number One, at the northwest end of the complex fronting northwest on East Jefferson Avenue, is shaped in a broad "U," with the base of the "U" facing East Jefferson. The arms of the building angle out in a single jog to afford additional river views. Building Number Two, to the southeast of Building Number One's southwest end, and ranged along the southwest property line, forms a long undulating line, broken into projecting and recessed-front sections, extending almost to the Detroit River. The zigzag plan allows for more windows and better cross-ventilation within units, and provides more units with water views as well. A long open courtyard extending from Building Number One (the U-shaped northwest building) southeast to the river separates Building Number Two (the long southwest building) from two additional buildings fronting on its northeast side. Building Number Three, the more northwesterly building, zigzags in a west-to-east direction. Building Number Four stands in line with the third, but closer to the Detroit River.

The buildings are all designed in a matching Georgian Revival style. The structure fronting East Jefferson Avenue is three-and-a-half stories tall, with a half-story basement level. The Jefferson Avenue facade has a projecting central section containing in each story two sets of windows on each side of the entrance, plus a window above the entrance. The front entrance on East Jefferson Avenue is set in a pilaster and segmental pediment wood frame and has a red steel door. The buildings all have limestone beltcourses running between the second and third floors, and the buildings' corners are marked by raised brick quoining. Sometime in the 1980s false metal louvered shutters were installed on many of the windows. The current windows are vinyl double-hung six-over-six windows. The smaller windows, double-hung four-over-four vinyl replacements, do not have decorative shutters.

The southwestern apartment structures have basement-level entrances that are topped by painted wooden entablatures and flanked by pilasters. Cast iron fences surround the lower level entrance areas. Basement level windows are horizontal three-over-three double-hung vinyl windows. All of the doors in the River Terrace Apartments' twelve entrances are painted red, and most are steel with a window in the upper half containing wire safety glass. There are brass Georgian-style sconces next to each entrance door. At the roofline, there is a simple cast stone coping. The East Jefferson Avenue front entrance features a contemporary backlit sign and decorative rocks. The building is set back approximately forty feet from the sidewalk of East Jefferson Avenue.

The garden terrace area is planted with elm, white pine, and birch trees and ewe, juniper, cedar, and box hedgerow shrubs. The terraced lawn is divided into different levels by staircases set into the slopes and sidewalks also subdivide the courtyard lawn both running from the northeast-southwest and southeast-northwest. At the river's edge today stands a small modern wooden gazebo. Various lawn furniture pieces occupy the terrace area, and picnic tables stand along the riverfront. Standing light poles were added down the center and through the cross section of the terrace at a later point.

Architect/Builder

Derrick, Robert O.; Gamber, Branson V.; Derrick & Gamber, Inc.

NRHP Ref# 09000121 • Data from National Park Service • Content available under CC BY-SA 4.0

Historical Photos

(13)Public Domain (Michigan filing for National Register of Historic Places)

Building Details

- National Register

- Listed 2009

- Ref# 09000121